Photographs of Okarito line the walls of our Montana house, even though Okarito is a place I hadn’t been back to in seven years. One photo is of a bonfire on a beach and is the landscape on this blog – just layers of flames then the sea, then a sunset, and finally a darkening blue twilight – and one is of a white moon over a lagoon, waters rippling with a midnight gust, that now hangs just to the right of our kitchen doorway.

I took that last photo on a night I went for a run just outside of town, after finishing the last of the dishes for the group of 14 I was traveling with. This was always my routine when we came to Okarito, no matter how late I finished in the kitchen. During a two-week guiding trip of New Zealand’s South Island, this tiny town of about 30 people on the West Coast was the only place we stopped for two nights, contracting the guests out to a local kayaking company early the first morning, while the guides got to have a slow start to the day. Usually that involved cracking the windows so that you could hear the sea, stoking the fire in the potbelly stove that kept the guesthouse warm, and putting the kettle on for another French press coffee, as we slowly wiped down the long Rimu wood table and enjoyed the novelty of loading up a dishwasher, before sitting down for a second, maybe a third cup of coffee.

Later in the morning we’d make a hot lunch for the guests as they returned, usually windblown and soaked, laying their jackets by the fire to dry as they ate grilled cheese sandwiches with tomato soup and talked about what they saw out there on the lagoon. In the afternoons they would go for a hike into the bushland above the town, a place that gave them a view of the Southern Alps if they looked one way, and then the Tasman Sea below them in the other direction. That’s how condensed the South Island is. In the afternoon, we’d starting prepping for the leg of lamb we’d have that night, with mint and horseradish sauce, beetroot relish, roasted potatoes and parsnip with rosemary from the herb garden. Wine bottles and glasses would line the table. I’d have candles out in seashells we’d collected on the beach in the afternoon sometimes along with the black sand-smoothed rocks you always wanted to pick up as you walked on the shore.

That full day always led to the latest night. The dishes were brutal. Big roasting pans heavy with lamb fat and a trifle dish half full of chocolate mousse. It would sometimes be midnight by the time I was done, with a 6:30 a.m. breakfast prepped for the next morning. It didn’t matter. My running shoes were always waiting by the door; my tiny camera ready to go inside a jacket pocket.

I lived for those midnight runs. Under stars visible through the vines and thick beech and Rimu trees above me. The tannic lagoon waters would be black as the night around me as I’d run across the bridge, listening to the brown kiwis call out to each other when I’d turn off my music, hearing the sound of my breathing and my sluggish steps on the empty road that wound for 10 miles to the main highway if I wanted to run that far. I never did. It was about the solitude. Feeling weightless in the dark. It was taking photo after photo, trying to get the shape of the fern just right, so that the moon over the water wasn’t blurred when the wind came up. It was that last smoldering pile of driftwood on the beach. That was what I was on a hunt to capture on those nights.

When I went back to Okarito in February it was in the light of a long summer day. There was rain but it was warm out. This time I took to the Trig Walk, the trail that goes up, where you can spot Hector’s dolphins – the smallest and most rare dolphins in the world – out at sea, and smell the Manuka tea trees, with their white flowers set against the turquoise waves behind them. The sea almost looked gentle from this far up.

I only had a few hours to come back to this town before I had to head back to pick up my husband and then head south, to our next fly-fishing destination. It was a fast, beautiful run to the top, where I always sent guests to have that double view of Westland and the Southern Alps with the sea behind them. I got a little emotional standing up there on my own, thinking about the last seven years since I had been to this place. And how different my life was now, on a completely different side of the planet, in a little mountain town far away from the ocean. And how I was okay with this.

I was only away for a few hours, but it felt like I had traveled back in time to a side of myself that used to go on trail runs all the time with a tiny camera in a jacket pocket. I don’t wish for that old life back – but it makes me remember to integrate that part of me dead determined to find rest and capture beauty in the places I drifted through. Even for two days a month.

Another reason I wanted to take a trip out to Okarito, was to buy this natural sandfly repellent that was made locally and sold at the kayak shop, just coming into town. It’s made of almond oil and citronella and it was on everything I wore and slept in, in the years I worked for Active Adventures. It was the scent of physical exhaustion, an obscene amount of freedom, uncertainty, exhilaration, heartbreak, mountain peak hope – all the ups and downs of those long, beautiful Southern Hemisphere summers that I was young enough to rise to, and just old enough to know not to take for granted.

I thought about this too: I don’t know if I consciously set up my life this way, but I always seemed to put myself in the path of people wilder and stronger than I was. Because of this – mostly to keep up – I think I became a little wilder and stronger. That idea has been around in my mind for many years, but I was reminded of this when I stopped into the kayak shop to pick up the sandfly repellent and to grab a coffee. Behind the counter was a guy, Baz, who had also worked at Active Adventures in the tail end of my time there. It made me really happy to hear that he had bought the kayak shop with his partner, Gemma, who I also remember as a guide who often had baked goods in tins that she’d open up and share from the end of her trips. As Baz made me a flat white and I reclined on the shop couch with a magazine – just like I used to do in those gorgeous mornings off in Okarito – I saw a tin, the same tin, with Gemma’s banana bread that I remembered her passing around, while we were unloading trailers and unfurling roll mats and sleeping bags. Baz remembered me not so much as a guide, but as a writer – that summer I worked with him and Gemma was the final one before I went back into journalism full time – and that made me feel known. Because that’s what I was, more than anything else. In those years, I was just hanging around a lot of those people who lived fierce lives, and they made everything around me expand. I’m guessing they didn’t even know I was quietly learning from them.

But I did learn. They introduced me to places like Okarito and showed me where one of my favorite authors lived, with the gate sign that read All Strange Dogs will be Shot on Sight. It was Jordz who reckoned the flat white at the kayak shop was the best in the whole South Island. It was Dodgy Mike who taught me to recognize the male and and female kiwi calls. The male will always sound like this: Soooo, I’m just heading down to the pub for quick drink before heading home… And the female response that rings out in the dark: The hell you are. You better pick up nappies and milk and be home ASAP.

It’s kind of magical and still a little bit hidden. If you find yourself on the West Coast and you’re going from Glacier to Glacier, and you see the turnoff to here and wonder what’s at the end of the road that seems to just go right into the forest and sea, this is what you will find.

If You Go

Okarito is about 15 km north of Franz Josef on the West Coast. From Highway 6, take the turnoff to Okarito Forks and drive 13 km to the township. There’s no shops or petrol stations out here, so make sure you fill up your tank and load up on groceries in Hokitika or Whataroa (though Whataroa is just a small convenience store – better to get what you need in Hoki) if you are coming from the north. Franz Josef would be the last stop to get supplies if you are coming from the south.

Staying Here

Okarito has beach-side camping at the Okarito Camp Ground and there are numerous Airbnb rentals like this one – my pick if I was staying in town, practically in the sand with views to the alps. This cottage has a fire bath in the back yard. I remember when it was for sale and a few of us had a peek around, wondering how feasible it would be to buy it and carve out a life out here. The Okarito Beach House, where we used to stay, is sometimes available, with rates starting at about $165 NZ, which is pretty reasonable for the space, the views and that beautiful long table with the woodburner stove.

What to do

Walking and kayaking are your main options for activities. A great place to start is at Okarito Kayaks for an overview of the area. Wander in, have Baz make you a coffee, have a slice of Gemma’s gluten free carrot cake, and you can either book a tour or hire a kayak independently to explore the Okarito Lagoon, the largest unmodified wetland in New Zealand and is the only nesting home in the country to white herons. There are three main walks that begin right in town – they vary from a 20 minute stroll around the wetland to a 3 1/2 hour return trip on the Three Mile Pack Track. I’d recommend at least fitting in the Trig Walk, which is about 1 1/2 hours.

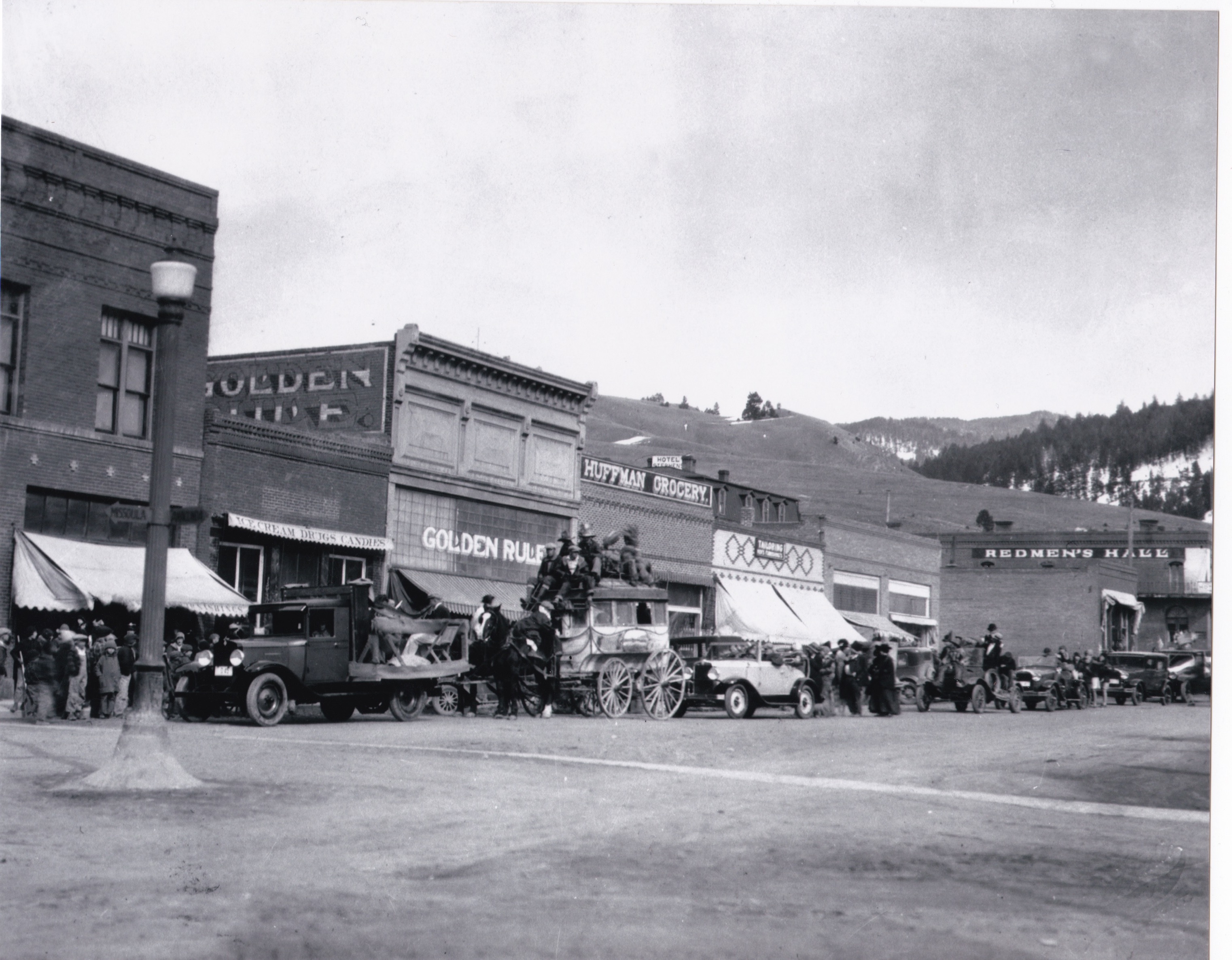

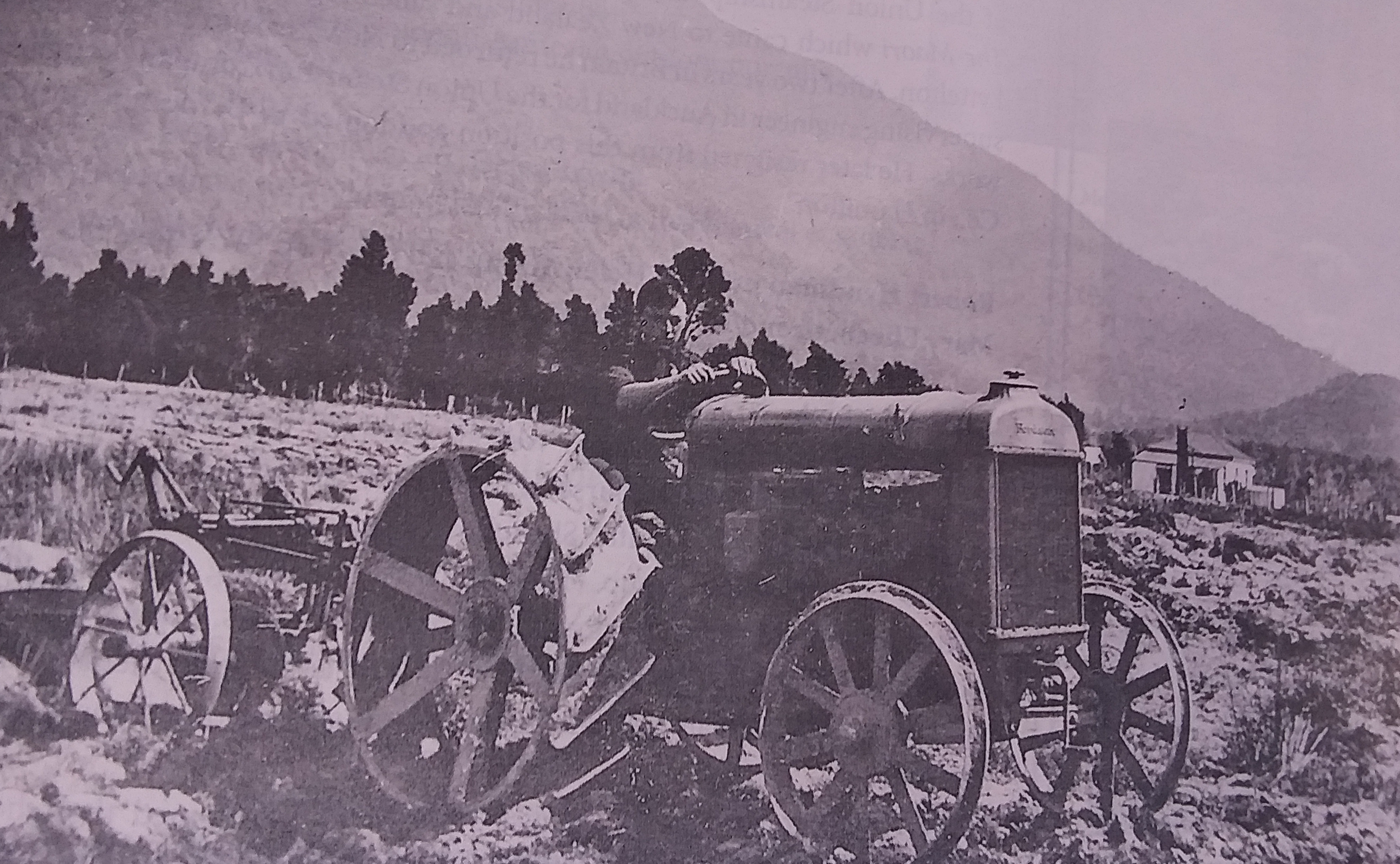

Have a chat at the kayak shop about music coming to town in the evenings. They are involved in booking artists for the historic Donovans Store, built during the 1860s during the first gold rush on the West Coast, when the population here was about 1,250 – 2,500 if you counted the outlying communities of Three Mile and Five Mile. My great aunties, Jessie and Minnie Gunn from Whataroa, used to be school teachers here before they married. Of all the hotels, theatres and bond shops that used to line the main street – The Strand – Donovans is the sole survivor and is actually the oldest building of its kind on the West Coast. It is used as a community hall and a music venue now – some fantastic artists come through to play here, so it’s worth checking in to see who’s on the event calendar. It might even be worth planning your visit around.