One of my favorite pictures taken in New Zealand’s South Island is of me, talking to two older men in a driveway. One of them in gumboots, the other in flip flops. Both of them were dragging their feet through the gravel, when the photo was snapped, trying to draw a map to the house where my grandfather may, or may not have, grown up in.

My husband took the photo of me from the passenger seat of our rental car, a vehicle loaded up with camping gear, sleeping bags, two hiking packs and his fly-fishing gear, a cooler and just enough clothes to get us through the three weeks we were there. I had left the car running.

We were in Whataroa – a town smaller than where we lived in Montana. When we stopped at the town hotel – which like all towns around here, doubles as the local pub – the windows were thrown open and pillows had been placed on the sills to air. The paint on the porch was peeling. The sign for Speights beer was faded. The sitting chairs out the back where we sat looked like old church hall seats that were torn. The yellow stuffing showed through the slits.

This was the town that my father’s father, Jim Hyndman, had grown up in, leaving for another farming community in the North Island where he met my grandmother, Gwyneth Griffith at a dance at the town hall. Jim died when my father was 15, leaving the Waikato sheep farm in Kiwitahi to my father’s older brother to run, while my father left for Australia, and then London to work in motorsport. Dad met my mother there. They ended up in California – her oceany homeland – where I was born. New Zealand became a fairytale, faraway land to my father’s children. A place in framed photographs across the carpet from the hallway closet until we were old enough to experience it for ourselves.

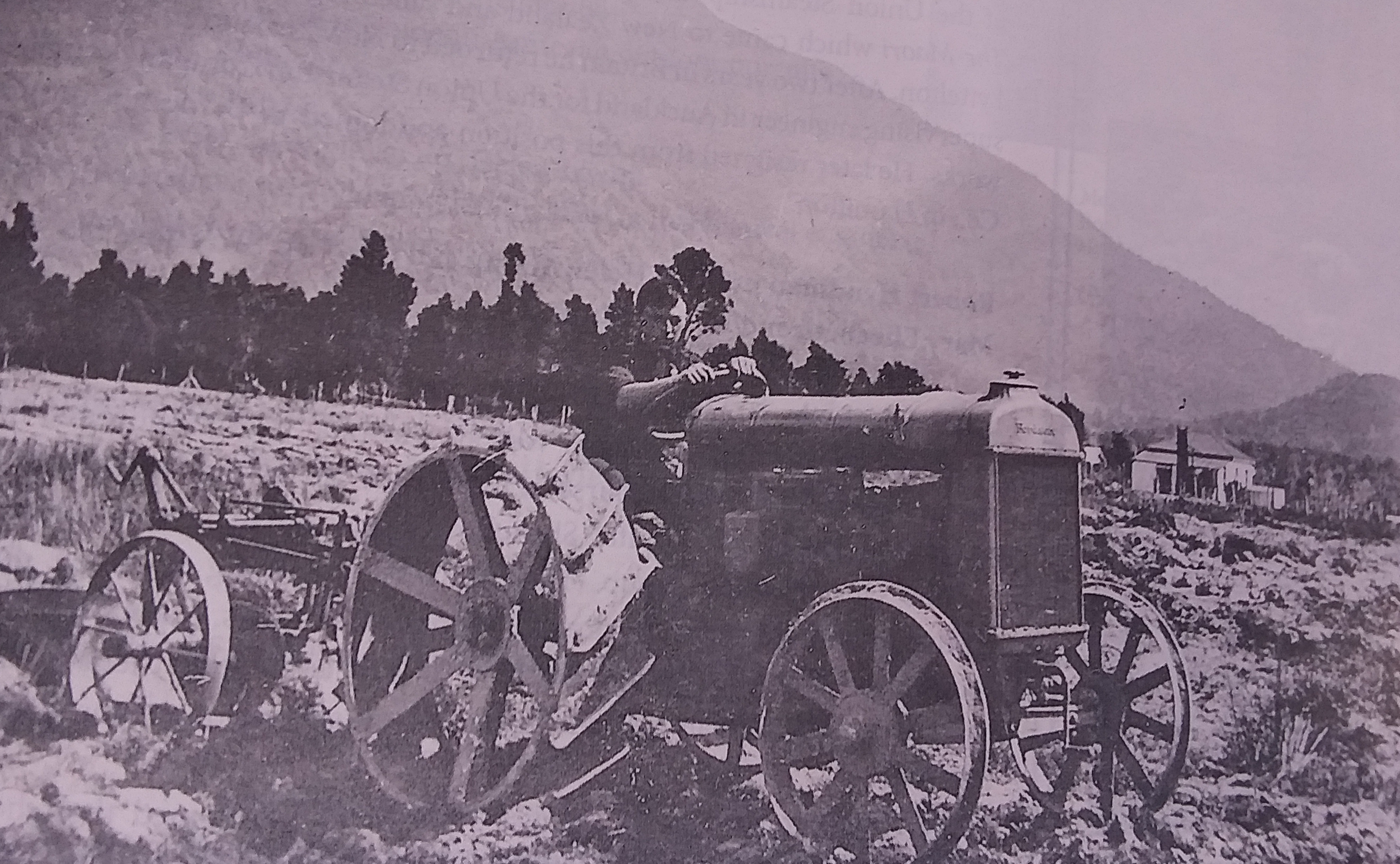

His memories, and my own, are of the farm in Kiwitahi, which stayed in the Hyndman family until my uncle and aunt retired more than ten years ago. The tiny town on the battered west coast of the South Island where Grandpa Jim had been raised was only known to us in old photographs. One was of the home in the 1890s, horses and a coach pulled up in front. Then in a faded, fuzzy photo in the 1920s, when it was still used as a boarding house. Another was of Grandpa Jim in a paddock, with the Hyndman home behind him, probably taken sometime in the 1930s. In this photo he was on a tractor and the mountains behind him were dense with native trees and bush. My father told me that this was the first tractor in this region of the West Coast, something I’ve never probed the accuracy of. It’s too cool a story to mess with. He remembers that the tractor went with Jim to the North Island and that it became a piece of playground equipment at the local school.

When I worked for a South Island-based hiking company, we would drive through this area on our way to coast and I’d point out the old family farm to clients. I always planned on one day coming back through this place. I’d have a beer at the pub. Maybe go take a picture of the old homestead. They might even let me inside for a look.

And this was the afternoon to finally do this, with John beside me. I pulled into the driveway I had been pointing out to people through the years, without being able to stop myself. I had saved a photo of Grandpa Jim on the tractor and of the Hyndman boarding house in the 1920s onto my phone.

Two brothers and their families were there in the sun on the front steps and listened while I explained myself. A barbecue was going on somewhere. Nineties rock was on. I could smell sunscreen. I was there to take a photo of the house that my grandfather had lived in, if that was fine with them, I said, feeling like I was a journalist again, apologizing as I was trespassing.One of the wives listened in, a hand over her eyes to block the late afternoon light. I could tell she would have invited us to stay for tea if I had lingered much longer.

They were friendly, but perplexed. They remembered the Hyndmans, they said, but as far as they remembered, the Hyndmans had lived on the adjacent property, not theirs. The brothers looked at the photos I showed them. Yes, one of them said. That’s the Hyndman house, but that’s on the other end of the road, where the highway used to go through and is now closed to through traffic. Look at the treeline, one of them said, holding up the photo of my grandfather on the tractor. Just like he pointed out in the photo, the wild bushland that went straight up behind us had a clear treeline and it was no where near where we were standing in their driveway.

A booted toe dragged a line through the gravel, hands pointed, and there was lots of talking over each other as the brothers discussed the best way I could get to the old homestead. It was still occupied, they said, and was one of the oldest standing houses in the community.

I got in the car, disoriented. It’s weird to have a piece of your family history all backwards, then explained back to you by a stranger who lives with that history in their backyard. Were the brothers wrong? Could there be more than one Hyndman house, as is common in farming families. Maybe my dad or I had looked at the map backwards or upside down. I wondered how that had happened as we drove back through Whataroa and to the other end of the same gravel road, following the directions they had given me, an eye on the treeline that defined the property below.

The old house was falling apart. When I walked towards what seemed to be the front, lined with boots and jackets, I could see that all the doors were open. I called out “hello?” – a few times, but all I heard was a few familiar strains of a song I couldn’t place at first. A strumming guitar. A few blurred minor keys. Then Bowie’s voice set the definitive tone for this sojourn into my family’s past in this place. My feet actually went step by step up to the top of the porch to the front door to a that haunting countdown, a searing, psychedelic guitar strain, then Check ignition and may God’s love be with you. I stopped when I saw a lone vacuum cleaner in a vast lounge room with just one lounge chair and a flatscreen television. Someone was in house. Maybe they were just in the shower. Maybe behind a parted curtain. But everything felt wrong and weird and I didn’t want to be standing on those front steps anymore, like the first victim in some indie horror film.

I walked back down to the car, turning around to take pictures with my phone, definitely in retreat. I didn’t know what to make of this house. It was definitely the workers’ quarters for an adjacent farm now. If this homestead had glory days, they were long gone. It felt like a run-of-the-mill, decrepit house that you’d see in any old town that you’d drive through and just think creepy.

It’s funny how ordinary history is – and how missable – when it isn’t in a framed picture in your family’s hallway. My dad contends that the brothers got it wrong. That the Hyndman house was on their property after all. Was it the foundation that their newer house had been built on in the 1970s? I just think my dad and I need to come back to this place and get to the bottom of this mess, so we can get our story straight. But this is why you take these side trips – to get a better idea of how your own lineage descends through the tree on a piece of paper. Sometimes it’s drawn for you in the gravel of a driveway.